“I’m just a poor boy, nobody loves me.”

Queen’s classic was the soundtrack to life (especially road trips) with our large-in-body-and-in-personality Maine Coon “starter child.” He was a very PRESENT kind of cat (not like the superior, aloof type); he met us at the door, slept with us, and was fairly sure he had equal say in everything we did.

But he sometimes went nuts. Not just ordinary nuts, you know, but run-around-the-apartment-so-fast-that-he-could-race-halfway-up-the-wall kind of nuts. And he hated the car, erupting with deep-throated, belly-aching meows for the entire five-hour trip back home. Once, when “Bohemian Rhapsody” came on the radio, the husband and I cranked it up and sang at the top of our lungs to out-catterwall the cat. He got quiet. And forever after, “Bohemian Rhapsody” was his song.

That song just fit him–a chiaroscuro of moods.

Music does that–fits a person or a situation or a place–in real life and, for many writers, in their fiction, too. Some writers are kind enough to give a reader the “playlist” for their work. Charles DeLint almost always tells what he was listening to as he wrote; he introduced me to Holly Cole’s Dark Dear Heart and the awesome Celtic band Lunasa when I read his novel The Onion Girl. Neil Gaiman says in his Afterword to American Gods that “without Greg Brown’s Dream Cafe and the Magnetic Fields’ 69 Love Songs it would have been a different book.” His most recent and most beautiful The Ocean at the End of the Lane was written to the soundtrack of Magnetic Fields’ Love at the Bottom of the Sea and lots of Leonard Cohen.

You can learn something about a character when you find the music that “fits.” You can use the “right” music to transport you to where you need to go in a story.

For Bohemian Gospel, I needed go to the thirteenth century. I wanted to hear what my characters would hear. I found Neidhart: A Minnesinger and His “Vale of Tears” (a collection of songs written by a court musician in the late Middle Ages) on Spotify. (You can get a taste of it here.) I also listened to a variety of Gregorian Chants. But it was Laura Marling and Iron and Wine who sent me deep into Mouse’s head and heart to help me feel her struggles and her wants.

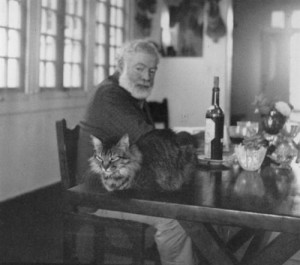

Apparently Hemingway listened to Bach. (He liked Maine Coons, too.)

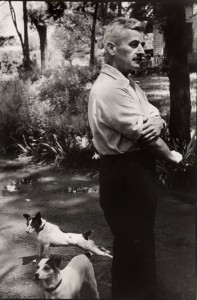

I wonder what tunes inspired Faulkner.

(Clearly, he was more of a dog person.)

But then . . .

“He’s just a poor boy from a poor family.”